Research

My research is motivated by three overarching questions:

- What is a system’s capacity to adaptively evolve in response to different selection pressures?

- What are factors that influence this capacity to adaptively evolve?

- How do we measure this capacity to adaptively evolve?

I think of evolvability (defined by Riederer et al. (2022) as the capacity of a (biological) system to adaptively evolve) as a useful framework to encapsulate all of these questions. However, evolvability as a field is fraught with disagreement, namely because there is confusion and debate on how exactly we should define it and how it should be measured. Hence, in my research, as I aim to address these three questions, I also hope to offer clarity to the evolvability research front by embarking on a mechanistic understanding of evolvability, using (pathogenic) microbes as my study systems.

At present, I focus on how mechanisms shaping the genotype-phenotype map of a given biological system enhance or constraint its evolvability. In other words, how do mechanisms that are involved in the flow of genetic information shape the phenotypic variation for selection to act on (which can affect a biological system’s evolvability)? Below, I describe some of my past, present, and future projects:

How mechanisms of evolvability have been studied in (microbial) systems

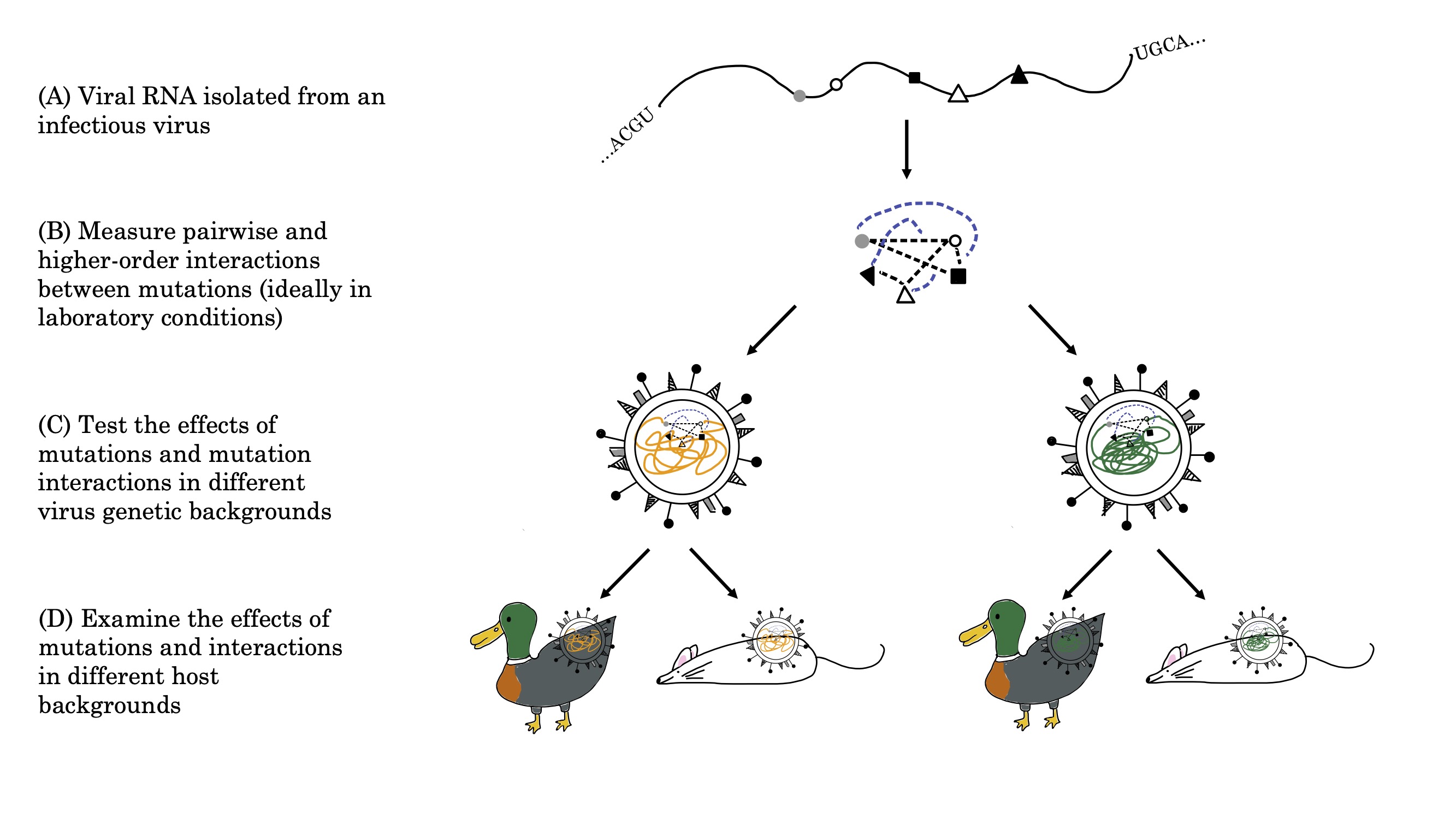

Part of the work in offering clarity to a field of study such as evolvability involves synthesising and understanding what has already been done in the field thus far. I conducted a systematic review of epistasis (where the combined phenotypic effect of mutations deviates from the constituent mutations’ individual effects combined) in viruses, where we discuss the need for genomic epidemiologists to actively incorporate epistasis in their work, and the implications of epistasis and viral evolvability.

Currently, I am working on developing and testing a framework for measuring evolvability in fitness landscapes, and I am excited to share more about that work as it develops!

Proteostasis as a mechanism of evolvability in microbes

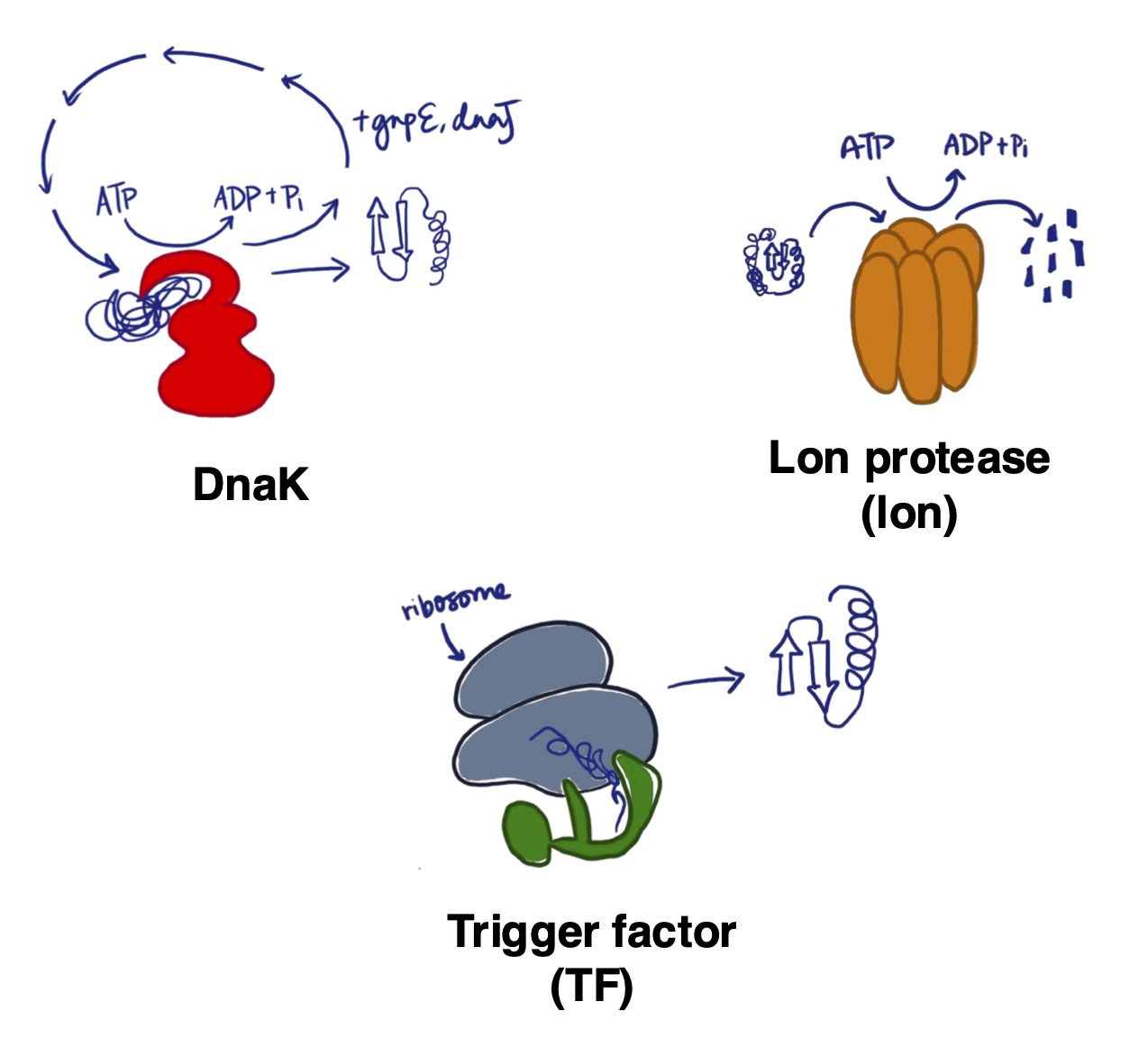

Proteostasis, or protein homeostasis, is a dynamic process in all living organisms that ensures that proteins are folded correctly, and that damaged proteins are degraded appropriately under various environmental conditions. Typically, a wide range of proteins - chaperones (which fold proteins), proteases (which break down damaged proteins) and protein translational machinery (involved in translating RNA into proteins) - are implicated in proteostasis.

Proteostasis is a fundamental, but underappreciated process of the genotype-phenotype map; it ensures that genotypic information is translated into appropriate phenotypes. Therefore, altering the proteins involved in proteostasis can alter the phenotypes expressed, which can have consequences for a biological system’s survival and reproduction (and by extension, its capacity to evolve). In my dissertation, I am interested in exploring how proteostasis can act as a mechanism of evolvability in microbes through experimental approaches.

This is currently ongoing work as part of my dissertation. Look out for more updates on this in the future!

E3ID (Epidemiology, ecology, and evolution of infectious diseases)

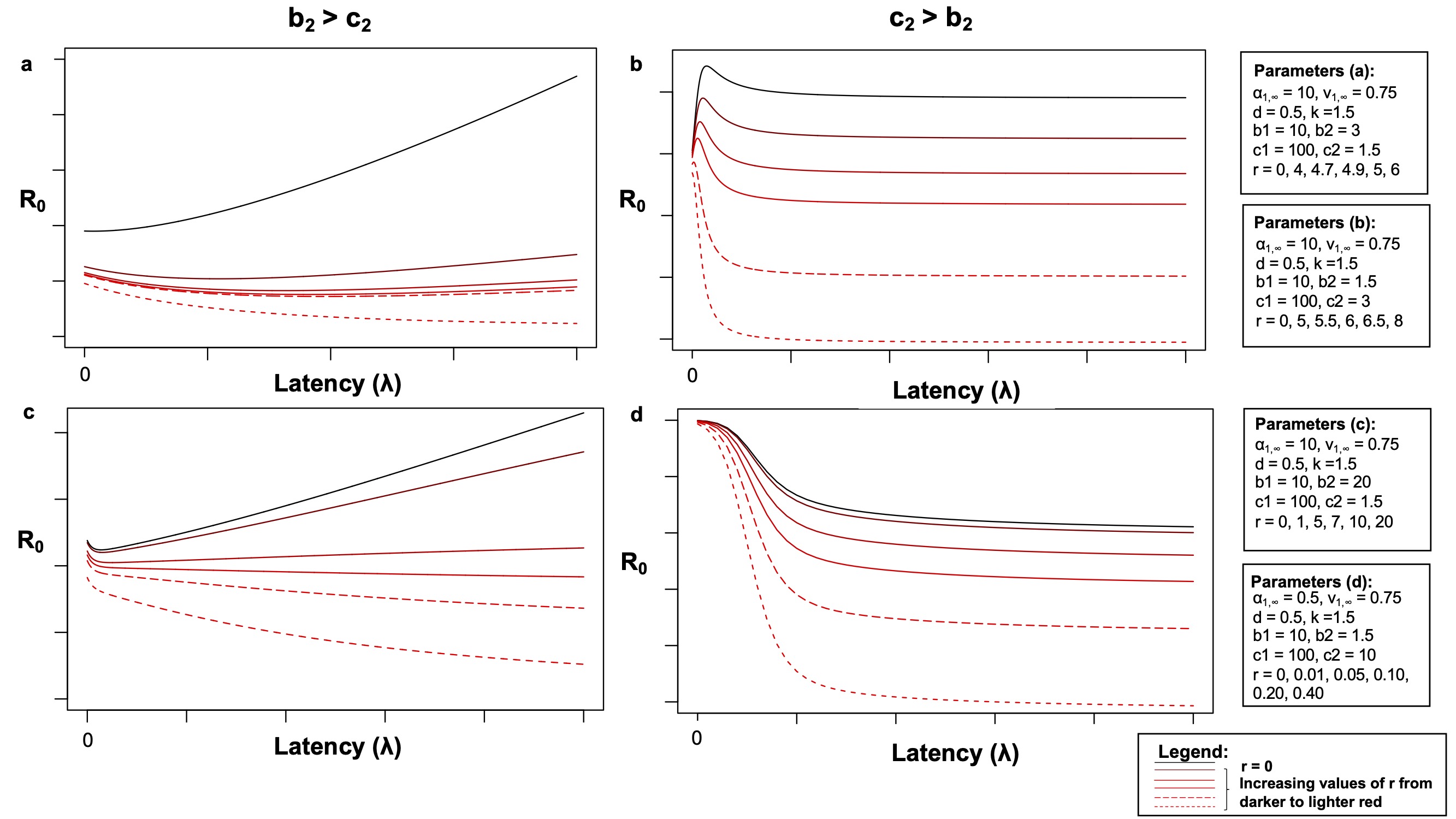

While not strictly part of the “evolvability” umbrella of my research interests, I am also generally interested in understanding and predicting the epidemiological, ecological, and/or evolutionary dynamics of infectious diseases. In my undergraduate studies, I used mathematical modelling to study how asymptomatic, infectious hosts that recovered without developing symptoms could shape the evolutionary dynamics of a pathogen. I was also involved in a study, where we have proposed new metrics to quantify the impact of social disparities on the epidemiology of disease outbreaks.